Antimicrobial resistance poses a significant threat to human health worldwide, with inconceivable consequences. In this long-read, GOLD asks how the pharmaceutical industry and governing bodies are planning to mitigate another seemingly imminent global health crisis

Words by Cheyenne Eugene

The growing threat of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is often referred to as a ‘silent pandemic’, inviting comparisons with the recent and ongoing COVID-19 crisis. However, these two crises require largely disparate cures. While the COVID-19 code is slowly being cracked, there is still much uncertainty and unexplored territory within AMR. Even though the issue has been pressing for years, industry experts are contending with many unanswered questions and are divided on how they imagine the future playing out in this landscape.

Investment issues

Historically, and, in fact, presently, pharma companies have been withdrawing from the antimicrobial drug development space, citing a lack of financial returns. Put simply, R&D is a resource- and finance-intensive activity, and newly developed antimicrobials face seemingly imminent resistance and redundancy, thus are viewed as a poor return on investment. According to Toby Cousens, Head of Hospital Business, UK, Pfizer, the unappealing landscape for investors “creates a challenging dichotomy of needing to preserve public health while making it difficult to recover the high costs associated with development”.

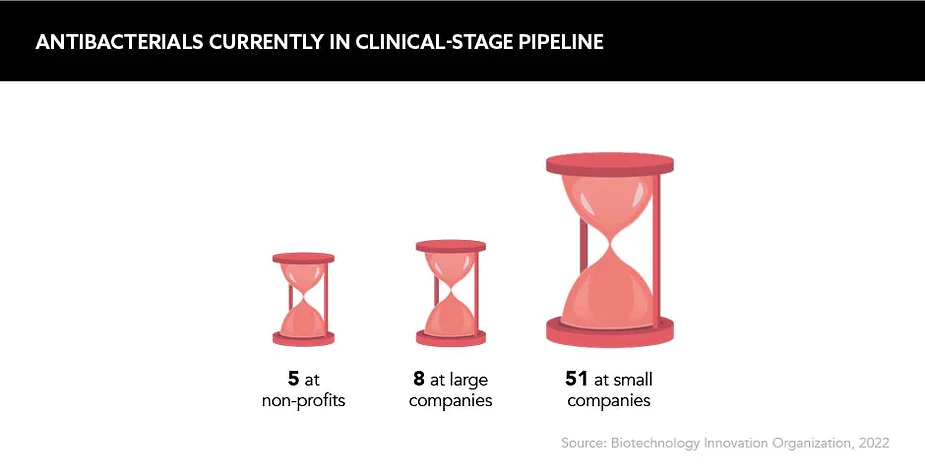

In the current framework, fear and reluctance to invest are well founded from an industry perspective. “Many small biotechs, which have proven to be lifesavers in diseases such as cancer and [vaccine development], have gone to the wall because of lack of interest and money to fund their [antibiotic] products, even if these have been approved,” explains Professor Colin Garner, Chief Executive, Antibiotic Research UK. Unfortunately, the writing is on the wall: recent years have seen a string of antibiotic-focused biotechs file for bankruptcy.

To truly combat AMR, science needs to think outside of the traditional antimicrobial R&D

In theory, the widespread development of new antimicrobials in their traditional form is therefore off the table. But what about the many existing antimicrobials, of which the majority are low-cost generics? Dr Boumediene Soufi, Global Head of Antimicrobial Resistance, Sandoz, believes that the current market framework combines the worst characteristics of both a commodity and regulated market, namely “commodity price levels but without any real freedom to adjust prices in light of changing supply and demand conditions”. If the current system is chewing up and spitting out antimicrobial developers, an overhaul is certainly overdue.

Offering incentives

It is well understood that new incentives are needed to build and bolster investment as well as encourage a commercial approach that rewards having antimicrobials in reserve for when they’re most needed, rather than undergoing immediate widespread adoption. This is where ‘push and pull’ models come in. “Push mechanisms are required to de-risk early investment into antimicrobial R&D and stimulate development of novel treatments,” explains Cousens. “Pull incentives will reward successful development at the level needed to improve commercial viability and to create a sustainable and robust antimicrobial pipeline.”

Cousens also notes that valuation and reimbursement reform are essential to ensure antimicrobials are adequately valued, maintain their availability on the market and can be widely accessed by patients. Both Soufi and Garner support this notion, with Garner pointing toward “a few green shoots, most notably the PASTEUR Act in the US and the UK’s pilot reimbursement scheme, which might allow better returns for new antibiotics”.

The UK’s pioneering scheme is the result of a collaboration between the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), NHS England and the Department of Health and Social Care. A milestone was hit earlier in June when the NHS announced the imminent rollout of two new antibiotics from Pfizer and Shionogi. These will be available using a subscription-style scheme likened to a Netflix account. A fixed annual fee of £10m is to be paid for access to the two antibiotics for 10 years. The UK is the first country worldwide to implement this payment model for antimicrobials.

In addition, Garner says he is struck by some of the other creative reimbursement solutions being proposed, such as “patent extensions on profitable products – extensions of patent life or a carryover voucher that recognises monies invested into antibiotic treatments”. These potential solutions are certainly a stride in the right direction, but Soufi warns: “There is much discussion of these concepts, but, to date, no general agreement on which approach to take and how to implement them”.

A G7 meeting in December 2021 explored how policy reforms could build a sustainable antimicrobial pipeline. The resulting ‘Finance Ministers’ Statement on Actions to Support Antibiotic Development’ stipulated that each G7 member commits to expediting their strategies and action plans, but with each market looking at different mechanisms to stimulate R&D. “There will be an added policy challenge in how we align these market-based approaches internationally,” explains Cousens. “If we have learned anything from the COVID-19 pandemic, it is that health threats such as these require true global equity.”

Although it is a priority for industry bodies and governments, factors such as access are woven tightly into the policy and investment web, and these must be considered as well – the consensus being that there is still a long way to go.

Bolstering R&D

Until recently, the narrative around antimicrobial R&D has been fixed on the ubiquitous fact that there have been no new classes of antibiotic developed for over 30 years, leading to rumblings of a ‘discovery void’. Some industry experts, including Soufi, disagree with this term and instead see the issues lying with the slow development process and the need to recognise the limits to what R&D can achieve on its own.

Conventional antimicrobial R&D is re-emerging but, overall, tradition is not triumphing and there’s a constant battle dominating the space. “Superbugs are emerging faster than new antibiotics can reach the market,” says Cousens. “To truly combat AMR, science needs to think outside of the traditional antimicrobial R&D.”

Superbugs are emerging faster than new antibiotics can reach the market

The potential saviour technology on everyone’s lips? mRNA. If vaccines based on this technology can become a first line of defence against pathogens, this would result in fewer infections and, ultimately, a decline in the use of already-over-prescribed antimicrobials. Misprescribing and misuse of antimicrobials by healthcare professionals and patients is a well-known driver of the looming AMR threat. However, despite being a promising alternative, Garner warns that as yet, “very few of these [mRNA vaccines] have been subject to evidence-based clinical trials”.

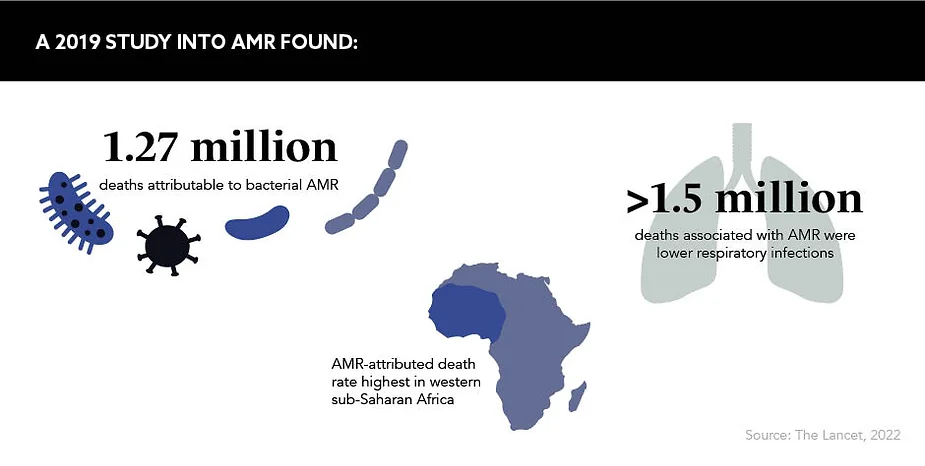

Another area of AMR research being increasingly harnessed is surveillance data. Building a pool of data will allow “healthcare experts to better understand and address resistance patterns”, according to Soufi. This is also highlighted in a study published in January 2022 in The Lancet looking at the global burden of AMR. It highlights “serious data gaps in many low-income settings, emphasising the need to expand data collection systems to improve our understanding of this important human health threat” across varied populations.

Public perceptions

Public perceptions around health have become particularly lucid over the past two years, although surveys suggest that this cannot be extended to the looming AMR public health crisis. “There is a massive public knowledge gap about this problem,” reveals Garner. According to industry experts, common misconceptions include the public believing that because they have never taken antimicrobials they are safe from getting a resistant infection, as well as the belief that antibiotics are effective against viral infections.

Cousens believes there is room for pharma intervention here. “Education is a key aspect in which the pharmaceutical industry can support,” he says, going on to highlight some of the programmes already in place. Among them is Pfizer’s ‘Superbugs: Join the Fight’ school campaign, which sends educational resources to over 1,300 schools across the UK to raise awareness of antimicrobial resistance, the role of vaccines and viruses and pandemics.

“The key message we need to get across is the unique nature of antibiotics as the backbone of modern healthcare,” Soufi urges. Additionally, he warns that if antimicrobials become ineffective, it will not just mean a return to fatal infectious diseases of the past, it will affect the safe delivery of millions of routine surgical operations as well as common procedures that weaken the immune system, including chemotherapy.

Partnership and collaboration

Without large, cross-border, cross-sectoral partnerships, the cause to tackle AMR will get nowhere fast. “This is too big a problem for any one player or country to tackle alone,” states Soufi, adding that the focus of such partnerships should be across the four pillars of the global response strategy: manufacturing, access, responsible use and innovation.

Partnerships already exist within these four facets, most notably the AMR Industry Alliance – the largest private sector coalition aimed at finding sustainable solutions to curb AMR – and the AMR Action Fund, which drives innovation with the goal of bringing two to four new antibiotics to patients by 2030. However, Soufi stresses the need for “a wide-ranging public-private collaboration effort that goes well beyond what is currently happening”.

There is huge scope for partnerships to develop and for all stakeholders to have productive discussions to better understand each other’s perspectives and work out the most effective courses of action. For Garner, one of the main opportunities is through the wide implementation of patient centricity. “Until patients are brought into the heart of the issue we will continue to drift,” he says.

Most are in agreement that the weight of the AMR crisis should not be shouldered by pharma alone, but instead requires concerted action from all. “There have been lots of fine words from bodies such as the UN, WHO and G7, but most of this is simply that: words,” says Garner, sharing the same frustration as many. Until the sector and governments can put their money where their mouths are, little action can be initiated. “The clock will inexorably tick towards 2050, when up to 10 million people might die globally from a drug-resistant infection,” warns Garner.

While local action can be employed by individuals, global initiatives need to be designed and implemented by industry, healthcare bodies and governments on an international scale – as Cousens neatly summarises: “Collaboration needs to be a global initiative with local action.”

The future

Pharma is still establishing its role in the joint effort against AMR. “Pharma companies need to recognise they have a societal responsibility to treat human disease and, in particular, antibiotic resistant infections,” asserts Garner. “COVID-19 has demonstrated that it is possible to find effective treatments for a pandemic very quickly – the same energy and finance needs to be ploughed into [new antimicrobial solutions].”

As AMR is a natural phenomenon that will also affect new drugs once they enter the market, it would be misguided to commit considerable resources to this area without upholding the other pillars of the global AMR response strategy. Soufi reveals where he thinks additional energy and finance ought to be poured – a place where it is not currently benefitting from much traction. “We need a more balanced approach that goes beyond the somewhat naive belief that new drugs alone will solve AMR,” he explains. “We often forget that one of the key drivers of resistance is the underlying burden of untreated infectious diseases

in regions such as sub-Saharan Africa.”

This demonstrates that while attention is turned most notably towards investment, policy and R&D, there are other areas pharma must target if AMR is to be tackled effectively: access, public understanding and the mining of surveillance data.

In the UK alone, 12,000 lives are lost annually due to AMR, which is equivalent to the number of deaths from breast cancer each year. Globally, this figure sits at 700,000 and, as of January 2022, AMR is the leading cause of death worldwide. The consensus is that the severity of AMR is being grossly underestimated. Imparting the solemn message shared by many, Cousens concludes: “The greatest misconception we as people can have about the threat of AMR is that it is a crisis lying in wait.”