The war in Ukraine has displaced patients and cut off care for those remaining in the country. How has the pharmaceutical industry and its relevant organisations responded to create healthcare continuity and prevent the loss of unnecessary lives?

Words by Isabel O’Brien

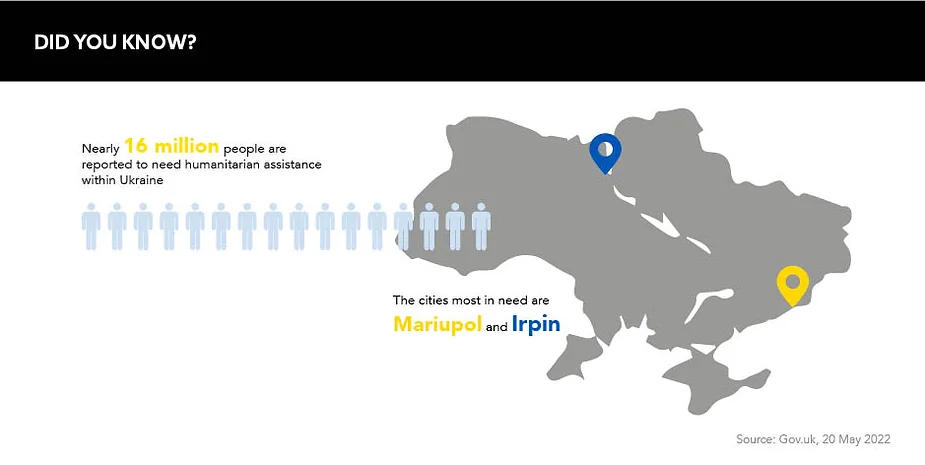

War causes unimaginable disruption to daily life, and the casualties extend far beyond those directly embroiled in the conflict. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has not only displaced a staggering 14 million people, and killed thousands of others, but it has jeopardised access to medical care for hundreds of thousands and ceased clinical research in the country.

While the pharmaceutical industry lacks the power to stop the conflict, evacuate patients to safety or rebuild shattered medical centres, it has been offering support in other ways to ensure unnecessary lives are not lost, and that vital research is not wasted because of the ongoing situation.

Humanitarian aid

The rolling news broadcasts that have served as a window into the war-torn cities of Ukraine have also cast a light on the hospitals desperately trying to continue care without access to the most basic amenities. The scenes invoke feelings of helplessness, but the industry has been providing humanitarian aid to support the healthcare professionals and patients that remain in the country.

Members of the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations (EFPIA) alone have donated huge sums to the cause, which is a trend that has been mirrored by other companies and medical organisations around the world.

For donations to be effective, companies and partners must also have a shared understanding of what is needed

“Members immediately focused on how to support the humanitarian relief effort,” says Dr Koen Berden, Executive Director for International Affairs, EFPIA. “It remains our members’ key focus.” So far, they have donated 23 million doses of medicines and €63m in financial support for Ukraine through direct support to Ukraine’s Ministry of Health, international NGOs, Direct Relief, and the EU’s civil protection mechanism.

Medicines donated by pharma companies include those for urgent care, such as antibiotics for those injured in conflict, “but also for chronic life-threatening illnesses such as insulin for diabetes and ongoing cancer treatments”, says Margo Warren, Head of Policy, Access to Medicine Foundation.

Shoring up supply chains

Another key focus has been creating channels for medicines and equipment to safely enter the country. “For donations to be effective, companies and partners must also have a shared understanding of what is needed,” says Warren. “This can include transportation and logistics, trained health workers, national regulatory requirements such as import licenses being met and the need for additional funds to address these issues.”

The coordination of emergency channels for medicine delivery has been spearheaded by the World Health Organization (WHO), but the industry has been offering support as needed. These networks are designed so distribution centres are set up in safer cities in Ukraine, then medicines are siphoned to the areas most under siege. Initially, these efforts were focused on supplying emergency medical care such an anti-tetanus toxoids, plus trauma and emergency surgery kits, but have since extended to vital medicines and treatments for other conditions.

But it’s not just imports that have been affected: before the war, for example, Ukraine accounted for 6.8% of Uzbekistan’s pharmaceutical industry imports worldwide, and the country supplies a small proportion to Georgia and Moldova, too. Needless to say, these exports, and others, have faltered, and alternative sources of medicine have had to be found.

Reinforcing clinical trials

The pharma industry has also faced the challenge of circumventing disruption to clinical trials in Ukraine. According to a report by the Access to Medicine Foundation, 13 clinical trial projects were taking place in the country in 2021, spanning seven different cancers, ischaemic heart disease, kidney diseases, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Alzheimer’s, lower respiratory tract infections and asthma.

“In the last decade, many companies have experienced difficulties with armed conflicts interfering with clinical trials,” says Warren. “In these cases, adaptations to the trials will often be needed to preserve the quality of the data generated by the trials, but, most importantly, the ongoing trial treatment should continue for the participants’ right to healthcare and safety.”

The issue is twofold: ensuring trials do not have to be abandoned due to dropouts and finding mechanisms to enable patients who have fled the country to still take part. Regulatory bodies have made allowances to prevent clinical research being wasted. “The EMA extended the COVID-19 regulatory flexibilities methodological guideline to the conflict in Ukraine to manage the missing data due to the drop out of patients from clinical trials in Ukraine,” says Berden.

In addition, in the case of multi-country trials, many patients have been relocated to alternative trial sites in other EU countries, so they do not have to forgo their place in the study and potentially sacrifice a cure.

Continuity of care for refugees

Pharma must consider more than just the plight of people still inside Ukraine. There are also the 14 million citizens who have been displaced and are now adjusting in new and unfamiliar healthcare systems.

“Companies should give priority to continuity of care by making essential medicine rapidly available and affordable, in appropriate cases, through ad hoc donations in countries hosting refugees or relevant and trusted humanitarian organisations,” affirms Warren. But the industry must go further than finance to help the displaced assimilate and gain access to healthcare as they did at home.

An example is an EFPIA initiative seeking to dismantle language barriers for Ukrainian people. “EFPIA is working with others, including the Polish authorities, on an electronic patient information leaflet (ePIL),” says Berden. “This ePIL will allow Ukrainian patients to scan the barcode on a pack of medicines and get instant access to the detailed medical descriptions in Ukrainian.” Other schemes pharma could back include securing digital versions of medical records from the ruins of medical facilities in Ukraine for those displaced.

Continuing collaboration

When quizzed about the Ukraine-Russia conflict and its impact on patients, a Kyiv oncologist told The Guardian that he estimates 15-20% of cancer patients will have had to discontinue their treatment as a result of the war. In addition, no new clinical trials have begun in the country since February 2022.

Even in these darkest of days for Europe, we see the health community come together

There is a sheer mountain to climb to create care continuity and a future for clinical research in a country so severely affected by war, but the world can take some small comfort in the way the international health community has come together to provide aid.

“Even in these darkest of days for Europe we see the health community come together to find all kinds of ways to help people in Ukraine or Ukrainian refugees arriving in the EU,” says Berden. “There are small rays of sunshine.” In short, excellent work has been done – but its continuation is vital.