Despite best efforts to combat social determinants of health during the pandemic, the postcode lottery is still causing health inequities today. How can the pharmaceutical industry push past this influential factor to deliver better outcomes to the patients that need it most?

Words by Jade Williams

The lottery: a game of chance played by many but won only by a select few. Typically, the winnings from these contests come in the form of money, but when it comes to the postcode lottery associated with health, the victor walks away with superior outcomes compared to their less fortunate counterparts.

In fact, health outcomes are determined more so by someone’s postcode than their genetic code, according to John Haughey, Global Life Sciences and Health Care Consulting Leader, Deloitte. Speaking at FT Live’s Global Pharma and Biotech Summit, he refers to this as “frightening”. Put simply, where you live matters. In fact, it can be a matter of life and death. How can the pharmaceutical industry tackle factors contributing to this skewed status quo to create better outcomes for more patients?

Local disparities

Levels of health equity underwent a notable shift as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. Improved efforts to create more equitable access to healthcare were noted the world-over as healthcare systems strove to combat the virus. GP surgeries, pharmacies and universities were utilised as testing and vaccination sites and pop-up clinics were constructed in more remote areas to ensure diagnosis and prevention was available to all.

Now, as the world moves on from the pandemic, healthcare systems and the industry must remain focused on creating better access to healthcare across the whole length and breadth of nations worldwide.

It’s not just country versus country, sometimes it’s down the road – just a change of a postcode

It comes as little surprise that different countries have varying access needs with regards to medicine. Nations such as Kenya, and other low- to middle-income countries, for example, experience lower levels of access to medicine than those more economically developed.

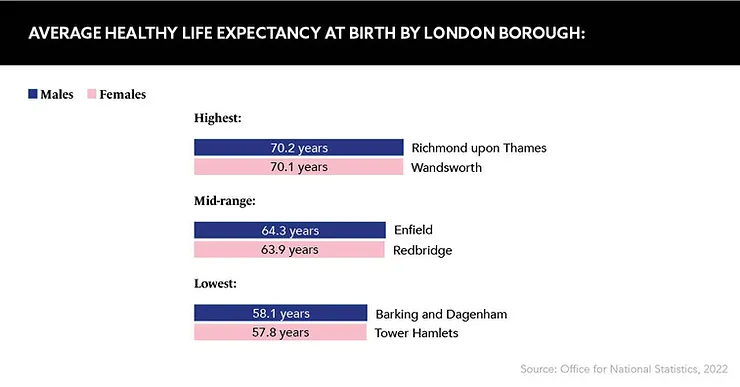

However, “what’s interesting is, it’s not just country versus country, sometimes it’s down the road – just a change of a postcode”, says Marie-Andrée Gamache, Country President, Novartis UK and Ireland, also speaking at FT Live’s Global Pharma and Biotech Summit. “If I go to south-east London, they may have 13 years less in terms of life expectancy compared to the rest of the UK,” she adds. “You don’t have to go far, and you don’t necessarily have to compare one continent to another.”

The best place to start

So, how can pharma cultivate change from this root? Laura Steele, President and General Manager, Lilly UK, Ireland and Northern European Hub, Eli Lilly and Company, also speaking at FT Live’s event, states that the industry needs to make clinical trials more accessible for people in areas where life expectancy is lower. To achieve broader representation from these often more disadvantaged neighbourhoods, she suggests companies “reimburse upfront for transportation because [lower-income participants] usually can’t wait on that reimbursement”.

Trial visits should also not be scheduled between the standard working hours of 9am and 5pm, Steele advises. This is so people “who are working and taking care of kids or elderly parents can actually come and partake”. Likewise, companies could facilitate enrolment by employing child and elderly care assistants to cover all bases.

Another consideration is to ensure representation on both sides of a trial. Patient trust is a critical factor in driving participation, and Steele suggests companies should “diversify the investigators so that you can recruit and have trust from a broader group of patients”. Hiring investigators from a diverse range of backgrounds could help more patients to feel comfortable partaking in clinical trials, particularly those in marginalised or lesser-acknowledged populations. Encouragingly, many pharma companies are already committed to achieving this goal. As Steele asserts: “All eyes are focused on making this happen.” Not only will this help companies build relationships with underserved communities, it can lead to more inclusive trial findings, too.

We’re not going to solve the issue on our own

On this point, Lu Zheng, Head of Value Based Partnerships and Digital Health, Europe and Canada, Takeda, expands further. Also speaking at the FT conference, she notes that companies have a responsibility to “make the clinical study available to the real patient population”, and emphasises the industry has a duty to develop new regulations “to really make sure clinical studies are designed for the drug’s end user”.

When developing trials, including patients affected by health inequities will pave the way for improved data overall, as this will ensure specific healthcare issues such as common comorbidities are accounted for in the final results

Crafting collaboration

Beyond the clinical stages, health inequities can be tackled by partnering with healthcare systems. While this task can be difficult, it is critical for the industry to collaborate with systems such as the NHS to improve health outcomes post-launch. “We’re not going to solve the issue on our own,” states Gamache. “It’s really about partnership and breaking that final frontier between life sciences, pharma and the system.” By forging collaborations between industry and healthcare, these systems can walk hand-in-hand to improve equitable access across all postcodes.

If one thing’s for certain, there is still a lot of change to be enacted within the industry. As Zheng suggests: “Sometimes it doesn’t take lots of new initiatives at all, but rather just thinking how you can leverage the existing process and get a drug to the end users more efficiently.” The pharma industry exists to help people, and patients, disregarded by the postcode lottery have an urgent need for improved access to positive health outcomes. Whether it be by ensuring drugs are made with specific patients in mind or improving access to healthcare facilities in collaboration with healthcare systems, more action needs to be taken.